RESPONSE #3 Juliette Kristensen

I was not at the last session of the 100 Hours Project, the Catherine Richardson session. Teaching commitments, I wrote apologetically to Leonie and Kate, teaching commitments. Across the Thames, as my fellow 100 Hours researchers were meeting in UCL’s Rock Room and pouring through the problems of the object in the historical everyday, I was standing at the front of a room in Goldsmiths where, my diary tells me, I was teaching a class on media archaeology.

I was not there.

And so, to ‘make up’, I read the responses: James on Gaps in Knowing, Doing and Believing; Emily on A Vocabulary for the Everyday; Kate on Experiential Objects; Sarah on Domesticity & The Dodo; Elin on An Anachronistic Gaze; Mat’s Reflections; Tullia on Absent Things; Katy on Environments; and I stared, with that peculiar level of attention we pay to our screens, at Florian’s screenprint/collage response.

I now know that this session was a more conventional one than The Order

of The Third Bird one. I know the discussion centred on historical reconstruction of domestic spaces of the early modern period through the use of early modern sources. I know the respondents were particularly struck by the idea of space in relation to their objects, the places their objects had been, the experiences their objects had had. And I know that Liz created a pencil rubbing of the group’s ten-pound note.

Yet knowing all this, I was not there.

I do not know where people were sat nor was I present to witness the intricate body language of twelve people in a room together for two hours. I don’t know who said what, nor how it was said. I have a little sense of the dynamic of the session, and little sense of the dynamic of the session in relation to our other sessions. You have to remember, I was not there.

However, I know extra-sessional – or maybe I should call them supra-sessional – things. I know that “design history has to take into account the stance of field hands as they swung the hoe”. I know that a recent auction of dodo bones put estimates of £7K-£10K on a leg bone, and £12k-£15k on a pelvis. I know Galton’s Weather Map Printing Blocks were used in The Times newspaper’s printing shop and that the weather first appeared in print on 1 April 1875.

The process of reconstruction, or re-enactment, is always a grasping, a reaching for the real and an extending towards some phantasmagoric sense of the authentic. But in this reaching for the real, a reaching that will never be able to grasp fully that which it seeks, other knowledges can be unexpectedly met on the way.

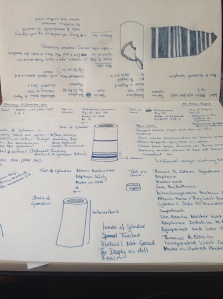

As I sat with my three Ediphone Tubes during a December handling session, accompanied by a pair of white gloves, an ink pen and a large sketch book, I began to sketch them out, to record forensically their dents and knocks, their breakages, their grooves and scratches, the graphic details of the labels, their patent information. I was there, with them, then.

It was a session of deconstruction, and one which strikes me now as one of translation, in that their material forms – which have always seemed to be an exemplar of objecthood, of being things that categorically and unashamedly stand in the way – exist as inscriptions of ink on paper.

And, for the large part, as I delve through the tubes’ earlier existence when they were ‘live’ technologies, researching the historical records for their conception, production and consumption, it will not be them in their materiality which I will carry with me from archive to archive, but rather their inscriptive presence, drawn out with ink on paper. They won’t be there.