RESPONSE #2 Tullia Giersberg

As a student of early modern literature I’m not usually accustomed to approaching texts or textual artefacts without some idea or expectation as to their content and meaning. It seems counterintuitive to surrender carefully honed analytical skills to the existential terror of not knowing or, worse, of not wanting to know. In the context of my own discipline, to look, pay close attention, and immerse myself in the peculiarities of the physical artefact without any notion as to what it might be, represent, or whether it will prove relevant to my immediate research objectives seems not only impossible but an inefficient way to go about the acquisition of knowledge, especially since online databases and full-text searching are rendering physical relationships with texts increasingly – and problematically – obsolete. Yet to encounter our ten-pound note on its own terms, to let it come into focus gradually via a series of mental exercises, was precisely what D. Graham Burnett and Sal Randolph encouraged us to do in our second group discussion. Surely, was my reaction at the time, a ten-pound note is a ten-pound note is a ten-pound note…?

I have to admit that even with the benefit of hindsight, and even though I enjoyed our collective experiment in attentive ‘encountering’, I’m not entirely convinced of the method’s merits or universal applicability. As other researchers on the project have indicated, their choices have been guided not so much by the object itself, but by its suitability to the purpose of the project. In other words, preconceptions about ease of access, utility, and interpretive possibilities had already mediated their response before they had encountered their object as a physical entity. My own decision-making process was influenced by similar considerations, which is perhaps why I found it particularly hard to distance myself in any meaningful way not only from our ten-pound note, but from my own object (I am trying to re-educate myself by thinking of it exclusively as item 4724 – with mixed results).

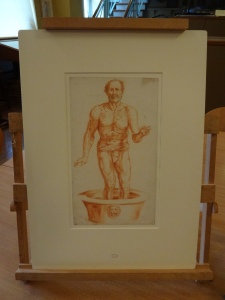

Because what I found when I first confronted The Death of Seneca is that it resists the total, quasi-meditative immersion in an object’s thingness which Burnett and Randolph advocate. Like the ten-pound note, it is essentially two-dimensional, consisting of a rectangular, carefully framed canvas of small size (in fact, the immaculate frame dwarfs the drawing by comparison) which is neither remarkable in itself nor particularly receptive to objectification – this is due partly to its flatness, partly because for conservatorial reasons the drawing cannot be touched. Instead, I found it mounted on a solid wooden stand which encases the drawing like a coat of armour and renders impossible any physical relationship with the object itself. Moreover, while raising the drawing to this quasi-vertical position should have facilitated an encounter at eye level, the resulting backward tilt had the contrary effect of releasing something steely and forbidding in the dying Seneca’s raised eyes as they seemed to meet and reject my own intruding gaze, articulating an unspoken barrier between the object and myself. Perspective matters. At the time, the experience reminded me of those unnerving visits to the zoo where one is never quite sure who is looking at whom, and has perhaps been the closest I have come so far in establishing anything like a rapport with the object, a rapport, however, mediated by the several choices of presentation which had already been made for me by the curators of the UCL Art Museum.

What did happen when I first encountered The Death of Seneca ‘in the flesh’ was the tangible sensation that it became real to me as an artwork and as an object only when I was physically aware of its presence in front of me. As William James writes in The Principles of Psychology, ‘Only those items which I notice shape my mind’. In Burnett and Randolph’s terms, I should really let the object notice me, let it guide my responses, and it’ll be my task over the next few months to find out whether this is possible. I’m not sure if my resistance to their method says more about it or about myself. But I suspect that I will have to return to The Death of Seneca many times before I’ll be able to ‘notice’ it fully, before I’ll have learnt to frame my mind to the object.

I think we shared a lot of the same responses and reservations Tullia, but your comparison of looking at animals in the zoo has really struck me. I’m going to give it another try!